Announcing that the great day of the lord is nearer than you think. O Come let us adore him - Luke 2:13

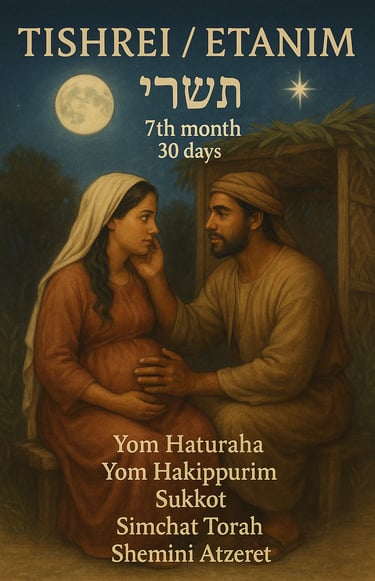

Understanding God's Calendar with Tishrei15

At Tishrei15, we explore God's nature through His biblical calendar, guiding you to recognize His divine appointments and their significance in your spiritual journey month by month.

The largest birthday celebration ever.

For those who say that Jews do not honor birthdays - https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/458473/jewish/Birthday.htm It is obvious that the lack of birthday references in Scripture would emphasize the one unique birthday honoured from Heaven, just not by His people. The honouring of a Jewish identity superseding Luke 2:10-14 is not the message that was delivered to us. Luke 2:17 falls on deaf ears in many Messianic Communities.

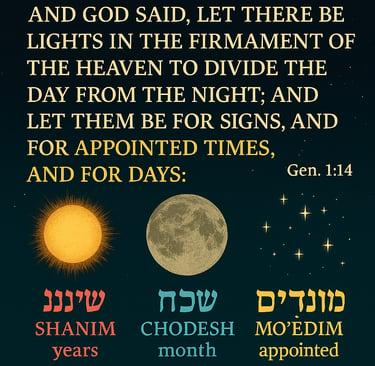

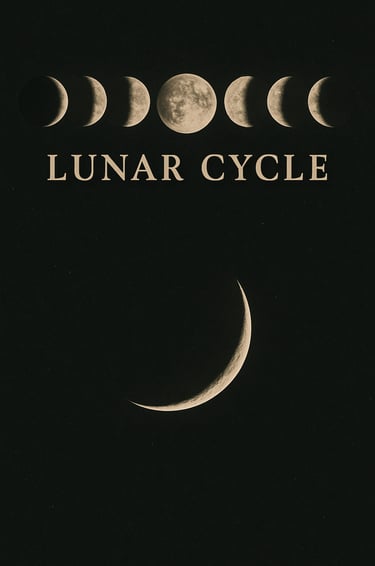

The Biblical Calendar does not begin with rabbinic conjecture or Gregorian reform. It begins with founding statements, not suggestions, in Beresheit, Genesis 1:14–16. There, the Creator speaks not in metaphor but in mechanism:

“Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for appointed times, and for days, and years.”

This is not poetic flourish. It is calendrical architecture. The two great lights, the Sun and the Moon—are not symbolic placeholders. They are named, tasked, and enthroned to rule over time. And the stars, those lesser sentinels, are summoned to join them in the governance of sacred rhythm. It is an offense to disregard the Lesser Light's rule in forming a calendar! Whether observed or calculated, the new moon occurs once, both methods converge on the same celestial event. To be clear, there is but one new moon each month. The only invalid method, including the observational or the calculated method would be if either resulted in either no new moons or more than one a month.

The Biblical calendar, though rooted in Hebrew covenantal identity, emerged within the broader matrix of the ancient Near East. Its architecture, lunisolar rhythms, intercalary logic, and seasonal alignment, shares structural affinities with Mesopotamian systems. Yet its theological orientation diverges sharply. Where Mesopotamian calendars were often tethered to astrological determinism and divine impersonality, the Hebrew calendar sanctifies time through covenant, not cosmos. Thus, the shared elements, new moon observance, agricultural cycles, intercalation, are not inherently Mesopotamian, but regionally intelligible. What distinguishes the Biblical calendar is its refusal to deify the heavens. The God of Abraham does not dwell in planetary omens or zodiacal fate. He speaks through appointed times (mo’edim), not astral signs.

The common points, then, are those stripped of astrological fatalism:

Lunar observation as a calendrical anchor, not a divinatory tool

Seasonal festivals tied to harvest, not celestial portents

Intercalary months used to preserve liturgical integrity, not manipulate cosmic forces

Time as covenantal encounter, it is somewhat spiral, not cyclical inevitability

In short, the Biblical calendar borrows the architecture but rewrites the script. It is not a Mesopotamian echo, it is a polemic against it.

What is a year?

It is a matter of no small significance, when regarding the reckoning of time as understood by the ancients, to observe that a year, termed Shanah in the sacred tongue (שָׁנָה), was not determined solely by the course of the moon, nor yet by the sun alone, but rather by a delicate harmony between the lunar months and the tropical solar year, that being approximately three hundred sixty-five days, five hours, forty-nine minutes, and twelve seconds. This reconciliation was not a matter of theoretical interest, but one of considerable practical consequence, for the year must needs be aligned with the seasons, and particularly with that of the barley harvest, which served as a pivotal marker.

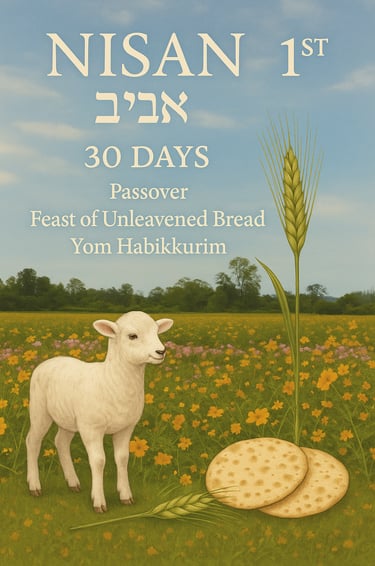

The Passover, or Pesach (פֶּסַח), a most solemn observance, was by divine ordinance to be kept in the month of Aviv, a term which not only denotes the ripening grain, but also the spring itself, the first and most hopeful portion of the year. In order to ensure that this sacred time should not drift into impropriety, intercalculations, those subtle and necessary adjustments, were made, owing to the undeniable reality that the heavens do not always adhere to tidy precision. It is worth particular note that no one, in their observance, ever perceived two new moons within the same month, a phenomenon which would have upended the entire structure.

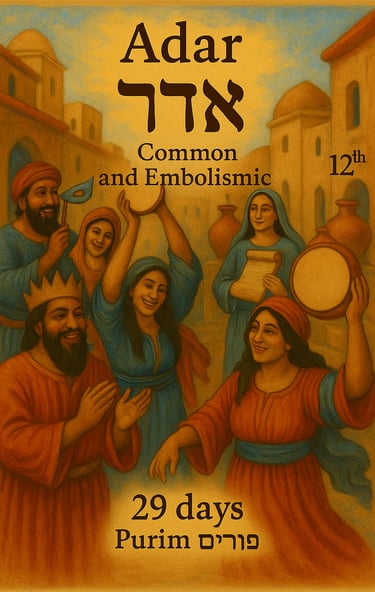

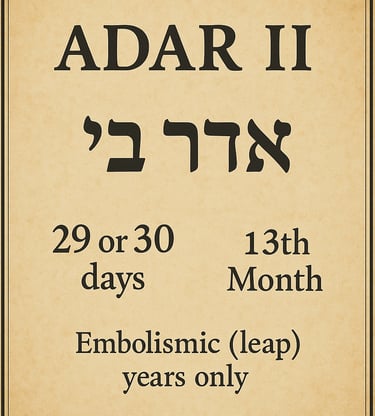

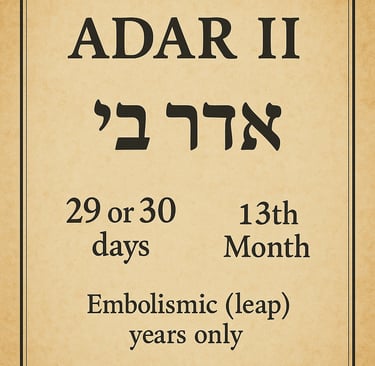

To prevent such disarray, the wise among them instituted what is known as the leap month, a second Adar, delicately inserted as the Twelfth month in those years that required it. Alongside this, the number of days in certain months, specifically the eighth, ninth, and thirteenth, was subject to variation. From these necessary alterations arise six distinct lengths of years, divided with elegant symmetry into two classes: three common and three embolismic. The common years consist of 353, 354, or 355 days; while the embolismic, that is, the inserted years, contain 383, 384, or 385 days.

The term embolismic, I must add, is derived from the Greek embolimos (ἐμβόλιμος), signifying that which is inserted or intercalated, a word whose elegance is matched by its utility. This system yields a cycle of nineteen years, after which the lunar reckonings resume their original correspondence. Though commonly attributed to the astronomer Meton of Athens, whose name now adorns this cycle, it is believed by many that such a method was long in use by the Sumerians, whose diligence in the study of the heavens cannot be overstated.

The present discourse shall concern itself chiefly with a span of two years, encompassing portions of the Hebrew years 3757 through 3759, which correspond to the Julian years 751 and 752 AUC. This would be 107 Metonic cycles ago. It is within this carefully chosen window that our attention shall dwell, examining how the sacred and celestial converged in the ordering of time.

Qumran’s use of “interpretation” to override Torah was projected onto Jerusalem as an accusation. This is a textbook case of sectarian projection: condemning others for the very innovation one is guilty of, while claiming exclusive fidelity to God’s law. The Qumran sect did not redact it (Exodus 12:20), but they used interpretation to override it, effectively replacing the moon with the equinox as the anchor. That’s why many scholars describe their move as sectarian sophistry, an attempt to claim obedience while actually re‑engineering the command. They were accusing Jerusalem of a interpretation when they were the ones doing the interpreting of a inaccurate 364 day year. They were the ones off by 1.242 days.

The Qumran sect's calendar was like someone keeping the family recipe name - “Grandma’s Bread”, but secretly swapping yeast with baking powder. They still call it “Grandma’s Bread,” but the bread no longer rises the way Grandma made it. Their bread rose 1.242 days to soon.

Then, to cover their tracks, they, projected, accused the rest of the family: “You’re the ones ruining Grandma’s recipe! Your bread is corrupt!” All the while, it is their own substitution that has altered the recipe. In stead of renaming the months to applets more derived from a solar foundation they kept the same names.

The Hebrew Months

As Hebrew months consists of either 29 or 30 days. The Hebrew calendar is unlike any other, and it presents, to many Western minds, a system rather difficult to apprehend. It is both lunar and solar, governed by a rhythm of observation and calculation. Days are not named, but numbered; months are both named and numbered; and the year begins not with January, but with Nisan, also called Avivonce the molad, or new moon, is sighted or computed. This is not speculation, but divine ordinance, first declared in Exodus 12:2 and maintained with devotion throughout the ages. In leap years, a thirteenth month, Adar I, or Adar Rishon, is inserted following the month of Shevat, extending the year to ensure Passover remains in its proper season. The necessity for this adjustment is born of astronomical reality; a lunation, after all, consists of approximately 29.53 days. The months are to be found in Ring J. Without such intercalations, the sacred festivals would drift from their appointed times. And as it was with the months, so too it must have been with the Mishmarot, those priestly courses of service, assigned in cycles of sacred duty, which appear in Ring G of this calendar. These, too, required adjustment to remain aligned with the Shabbat and the lunar cycle. The calendar thus honours both the observation and calculation of the new moon, methods which are not in conflict, but rather two instruments in faithful harmony. Opposition to the calculated method would be valid only if it yielded either no new moon in a given month or more than one, neither of which occurs. This is the heritage of the tribe of Issachar, of whom it is written in I Chronicles 12:32, that they understood the times and knew what Israel ought to do. It was not the sect of Qumran, but Issachar, whom the Torah entrusts with this sacred responsibility. Arguing that the calculated method stands in opposition to observational practice would hold validity only if it failed to produce a new moon in a given month, or if it rendered more than one new moon per month.

The Lesser Light

This additional month also called Adar is labeled a variety of ways by chronographers. It is inserted in two forms of either 29 days or 30 days in Embolismic years. Some times called V'Adar, Second Adar, Adar bet. It is inserted after Shevat.

The Week

The formation of a unit of time that is a division of month is ancient and existed in many cultures. The Akkadian term "šapattu" referred to the full moon or a rest day, and it's attested in texts from the Hammurabi period (~18th century BCE), though its exact calendrical function is debated. The text of Bereshiet (Genesis) 1:3 through 2:3 are of what the LORD God of Israel pronounced.

The Day

Days of the Week

Biblical Reference. Ordinal Day (English). Hebrew Day (Hebrew Script)

Genesis 1:5 "the first day" יוֹם רִאשׁוֹן

Genesis 1:8 "the second day" יוֹם שֵׁנִי

Genesis 1:13 "the third day". יוֹם שְׁלִישִׁי

Genesis 1:19 " fourth day" יוֹם רְבִיעִי

Genesis 1:23 "the fifth day" יוֹם חֲמִישִׁי

Genesis 1:31 "the sixth day" יוֹם שִׁשִּׁי.

Genesis 2:2-3. "the seventh day" (Sabbath). יוֹם שַׁבָּת

In the sacred account found in Beresheit, that is to say, the Book of Genesis, from chapter 1, verse 3, through to chapter 2, verse 3, the days of the week are identified solely by ordinal designation. No names are bestowed upon them, save for the final day, which alone is honoured with a title: it is called Shabbat. The Scripture presents these days in the most direct and unembellished manner, each one commencing with the setting of the sun and concluding with the next. As such, the duration of each may vary. It is worthy of note that while the Greek and Latin traditions do indeed possess names for the days of the week, such nomenclature is curiously absent from their respective translations of the sacred text. English translations, too, have followed suit. The Biblical custom of employing ordinal terms has been preserved by the translators, though it must be observed with some regret that such fidelity has not extended to the realm of theology, wherein the convention appears to have been much neglected.

The Mishmarot

or

Ma'amadot

The divisions of the priesthood, arranged most judiciously into twenty-four distinct and named courses, appear in biannual rotation and are faithfully inscribed upon the left margin of the calendar, encompassed within what is designated as Ring G. These courses, or Mishmarot, recur with constancy each year, a fact well-attested by numerous references found throughout the Mishnah, which speak with singular clarity upon the matter. It is worth observing, with no small degree of interest, that in the earlier portion of Ring G, these names are rendered in the sacred tongue - Hebrew -while in the latter half they appear in transliterated form, likely for the ease of those less conversant with the original script. This careful intercalculation is by no means incidental; rather, it is an intentional safeguard, designed to forestall the sort of temporal drift that might otherwise afflict the calendar's other features, were such precautions neglected. Moreover, a point of some importance is made in the First Book of Chronicles, chapter twenty-four, verse nineteen, where a significant clarification concerning the Mishmarot is conveyed. That being, that these were their appointments in their service, to come into the house of the LORD according to their order—an arrangement that was not only established but preserved. Indeed, it is most noteworthy that this same arrangement is employed by the Evangelist Luke in the opening of his narrative, as found in chapter one, verse five. There, with a precision most admirable, he makes mention of the course of Abijah, a reference not incidental, but deliberate, serving as a chronological marker by which the attentive reader may trace the unfolding of events which follow, and which, in due time, culminate in the birth of Yeshua, now more widely known by the name Jesus. Such a detail, though it may appear modest at first glance, is in truth a linchpin of sacred chronology, weaving together the priestly order, the prophetic expectation, and the providential moment. It stands as a quiet but profound affirmation that the service of the Temple, its cycles and divisions, were not merely relics of a former age, but instruments yet employed in the grand orchestration of divine purpose. It must be observed that, just as the calendar is subject to intercalation, so too must the Mishmarot be adjusted accordingly, in order to remain in harmony with the proper reckoning of years. The practice of such alignment was not merely incidental, but thoroughly established and faithfully observed. This necessity compels the use of a system, indeed, a device, by which the periods of collective service might be so ordered as to accommodate the intercalary adjustments with both accuracy and reverence. This practice, however, was never embraced by the Greeks or the Romans, who regarded the Priesthood as possessing no particular relevance; nor was it continued by the Rabbis, in their calendar, following the dissolution of the Priesthood at the hands of those same Romans. Indeed, the failure to acknowledge that the Priesthood, and the High Priest in particular, yet retain a present connection, as but a shadow of the Heavenly reality, is a matter quite lost upon the traditions of the West. The sacerdotalism of the Catholic Church, with its elaborate liturgical structure, as well as the Rabbinic Machzor for Yom Kippur, serve rather to obscure than to affirm the enduring significance of the Biblical Priesthood.

Mishmarot Intercalculation Formula: "Mishmarot Reset Schema"

Variable Terms

Core Anchors

A₁ - Nisan/Aviv 1 (date + weekday), annual reset point

T_R - Threshold to Rishon (days from A₁ to first Yom Rishon, 0–6)

Week₁ start - A₁ + T_R

Year Type

E_y - Year type

C_def (Common Deficient, 353 days)

C_reg (Common Regular, 354 days)

C_ab (Common Abundant, 355 days)

L_def (Leap Deficient, 383 days)

L_reg (Leap Regular, 384 days)

L_ab (Leap Abundant, 385 days)

Month Variables

M - Month count (12 or 13)

MM - Month subscripts

M_n (Nisan), M_i (Iyyar), M_s (Sivan), M_t (Tamuz), M_av (Av), M_el (Elul), M_ti (Tishrei), M_ch (Cheshvan), M_k (Kislev), M_te (Tevet), M_sh (Shevat), M_ad (Adar), M_ad2 (Adar II, leap only)

days(M_x) - Day count (29 or 30, per E_y)

wk(M_x^start) - Weekday of first day of month x

wk(M_x^end) - Weekday of last day of month x

Wm_x - Full weeks in month x (4–6)

D_x - Spillover days in month x (0–3)

offset_x - Days from month start to next Yom Rishon (0–6)

carry_x - Spillover offset inherited by next month

Weeks and Rotations

W - Total weeks in year (50–54)

Ms - Mishmar mapping function (24 courses cycling week by week)

N_i - Names of the 24 priestly courses (i = 1..24)

Mc - Metonic cycle index (1–19)

Moed Variables

Mo_{x,d} - Festival in month x starting on day d

L_Mo - Length in days (single, multi, Shabbat‑bounded)

T_Mo - Type flag (single, multi, Shabbat)

S_Mo - Shabbat constraint (true/false)

wk_start(Mo_{x,d}) - Start weekday

wk_end(Mo_{x,d}) - End weekday

d_end - End day in month x

C_Mo - Cross‑month carry (if festival continues into next month)

W_Mo - Weeks covered by Moed

Solve Operator Table

Variable Formula / Rule

T_R (Threshold to Rishon) (wk(first Yom Rishon)−wk(A1)) 7(\text{wk}(\text{first Yom Rishon}) - \text{wk}(A₁)) \bmod 7

wk(Mₓ^start) wk(Mx−1end)+1 7\text{wk}(M_{x-1}^{end}) + 1 \bmod 7; for Nisan: wk(A1)\text{wk}(A₁)

wk(Mₓ^end) wk(Mxstart)+days(Mx)−1 7\text{wk}(Mₓ^{start}) + \text{days}(Mₓ) - 1 \bmod 7

Wmₓ (Weeks in month) ⌊days(Mx)+offsetx7⌋\left\lfloor \dfrac{\text{days}(Mₓ) + \text{offset}_x}{7} \right\rfloor

Dₓ (Spillover days) (days(Mx)+offsetx) 7(\text{days}(Mₓ) + \text{offset}_x) \bmod 7

W (Total weeks) ∑xWmx\sum_x Wmₓ (+1 if spillovers add a week), constrained to {50–54}

Ms(w) (Mishmarot rotation) Ms(w+1)={Ms(w),if Adv(w)=0 \[6pt](Ms(w)+1 24),if Adv(w)=1Ms(w+1) = \begin{cases} Ms(w), & \text{if } Adv(w) = 0 \ \[6pt] \big(Ms(w) + 1 \bmod 24\big), & \text{if } Adv(w) = 1

days(Mₓ) fEy(x)f_{E_y}(x) (month length function from year type)

wk_start(Moₓ,ᵈ) wk(Mxstart)+(d−1) 7\text{wk}(Mₓ^{start}) + (d-1) \bmod 7

wk_end(Moₓ,ᵈ) wkstart(Mox,d)+(LMo−1) 7\text{wk}_{start}(Moₓ,ᵈ) + (L_{Mo}-1) \bmod 7

d_end (Festival end day) d+LMo−1d + L_{Mo} - 1

C_Mo (Cross‑month carry) max(0,dend−days(Mx))\max(0, d_{end} - \text{days}(Mₓ))

W_Mo (Weeks covered by Moed) ⌈LMo+offsetw7⌉\left\lceil \dfrac{L_{Mo} + \text{offset}_w}{7} \right\rceil

Compact Year Output

Y={A1, TR, Ey, Mc, MM, days(Mx), wk(Mxstart/end), Wmx, Dx, W, N1..24, Ms(w), Mo tuples}Y = \{A₁,\, T_R,\, E_y,\, Mc,\, MM,\, \text{days}(Mₓ),\, \text{wk}(Mₓ^{start/end}),\, Wmₓ,\, Dₓ,\, W,\, N_{1..24},\, Ms(w),\, Mo\text{ tuples}\}

The biblical calendar begins with Nisan, the month of redemption. It was in this season that Israel was brought out of Egypt, and so the year itself is anchored in deliverance. On the night of Passover, lambs were slain, blood was placed on the doorposts, and the angel of death passed over. This was not just a feast; it was the birth of a nation, the first breath of covenant life. The calendar itself was anchored here, in redemption. It is important to note that this reckoning of time was entirely biblical and covenantal. Later systems like the Julian calendar, devised under Rome, did overlap historically with Jewish life in the Second Temple period, but they were a completely separate context. The Julian months were civic and imperial, not covenantal, and they did not define Israel’s sacred rhythm. From that night, the journey unfolded. Weeks later, at Shavuot, the people gathered at Sinai. Thunder rolled, fire descended, and the voice of God gave Torah. Redemption was followed by instruction, freedom was not aimless, it was bound to covenant law. The calendar carried them from deliverance into discipline, from Exodus into revelation. Again, this cycle was independent of Roman civic timekeeping; the Julian calendar may have ticked along in the empire, but Israel’s months were counted from Nisan, not from January or March. The long summer stretched into wilderness wandering. Days of testing, manna from heaven, water from the rock, the rhythm of dependence. The months marked not abundance but trust, as the people learned to walk with God in barren places. Here too, the reckoning was covenantal, not imperial. The Julian calendar existed, but it was external to the biblical narrative, a civic overlay that never defined the covenant’s seasons. Then came the autumn, the time of Succot, the feast of booths. Here the people remembered their fragile shelters, yet rejoiced in the harvest gathered in. It was the season of in-gathering, the culmination of the year’s cycle. God had redeemed, instructed, sustained, and now gathered His people in joy. And while centuries later the Gregorian calendar would replace the Julian in Christian Europe, it must be remembered that neither system was present in Moshe’s day. They were wholly different contexts, devised for imperial and ecclesiastical purposes, not covenantal rhythm.

This is the flow of the biblical calendar: redemption first, then instruction, then wilderness, then harvest. It is a story written in time itself, a covenant woven into months and seasons. To begin the year in Tishrei would invert the tale, starting with judgment and harvest, pushing redemption into the seventh month. But the Scripture insists otherwise: the year begins with freedom, with Passover, with the God who redeems before He judges, who saves before He gathers.

מִשְׁמָרוֹת

Calendar

Faith

Nature

contact@tishrei15.com

+1 941-289-4930

© 2025. All rights reserved.